The “JFDI” era might be over, but do we really need to talk about mental health all the time?

Have we become so obsessed with our mental health and work life balance that our companies must take care of us at all cost?

A couple years ago, one of my managers told me that she didn't feel comfortable when I challenged and asked me not to do it. My answer was pretty straight forward:

“What does it have to do with me? If you are a manager, aren't you supposed to overcome your own insecurities in order to manage people?”. She looked bewildered and started raising her voice, saying: “As your manager, when I ask something, you must listen and execute!”.

Well, it wasn’t long before I was asking how many management courses she had attended, and what she had learned from them. Outraged, she abruptly answered that it was not relevant to this conversation. I couldn't disagree more and just like that, Nabil left the call.

These types of interactions exemplify perfectly the pre-pandemic world and how the lack of emphasis on management, and to a broader extent, on mental health was rampant. In fact most of the millennials built their career in a “work hard, play hard” work environment, dominated by the sacrosanct motto - JFDI and do not ask questions!

In a previous article, I covered the reasons why supposedly Good people can become bad managers, and what businesses can do to support the development of their employees, and nurture a work culture environment based on trust and transparency.

However, nowadays it seems impossible for companies (big or small) to turn a blind eye to the impacts of poor mental health from a productivity and talent retention point of view.

According to a survey conducted by Spill Chat, which analysed the answers of 1,000 UK employees in SME across a range of industries to see how mental wellbeing has shifted over the pandemic years, we can see that:

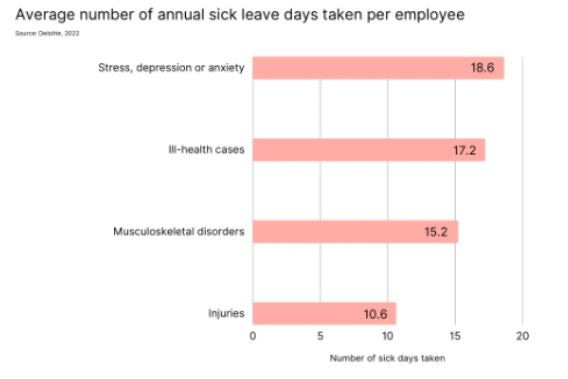

Poor mental health is still the main cause of sickness absences in the UK. Around 50% of long-term sick leave is due to stress, depression and anxiety.

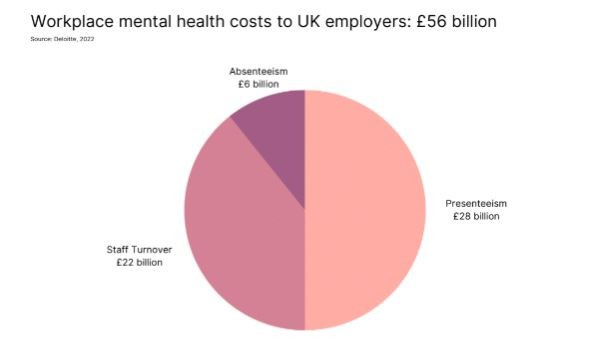

Poor workplace mental health costs UK employers around £56 billion every year. Costs have risen by 25% since 2019, and a staggering 47% of employees display ‘presenteeism’ (showing up for work without being productive due to poor mental health).

Interestingly, the survey also revealed that:

89% of employees with mental health issues say it impacts their working life. More than half of these have considered resigning from a job because it negatively impacted their mental wellbeing.

Women who work full-time are almost twice as likely to have a mental health problem than their male counterparts

Over a quarter of employees say they can’t switch off and relax in their personal time, hinting at increasingly blurred work-life boundaries since the pandemic.

The mental health of ethnic minorities has been disproportionately affected by the pandemic, leading to higher staff turnover rates (35%) compared to white employees (26%).

30% of LGBTQ+ employees say they are ‘extremely’ stressed on a daily basis compared to less than 2 in 10 of those who do not identify as LGBTQ+

As if we didn't have enough data, I then turned to my best friend, Google, asking it to show the past 10 years of trends in the UK, looking for key terms such as “mental health” and “wellbeing at work” and the results showed that searches for these topics are booming! The figures simply don’t lie!

Like most things in life, the beginning is crucial. When it comes to mental health at work, it all starts with a good induction. The purpose of an induction is to support employees as they settle into their new role in a new organisation, so it should include some of the below:

An overview of the organisational history, structure, visions, culture and values

An introduction to the business, colleagues and important stakeholders

A clarification of the job description including title, roles and responsibilities

An induction with HR and IT teams, as well as a setup of workstation

An overview of upcoming key dates and events

As some of you know, we have recently onboarded new apprentices, and without sounding like I am fawning, I am proud to see what we do at Penna to include new joiners whether it is the warm and personalised “Good morning” from our lovely Sharon, the welcome message on our TV screens or the support of our HR team. We do work hard to ensure everyone feels truly included. Seriously well done us!

So far so good but wait a second…

During a recent networking event, I bumped into some ex-colleagues, some of whom I have not seen for years. As the evening went by, and prosecco was poured, we exchanged stories and jokes and discussed how the past 3 years took a toll on our wellbeing. Unsurprisingly, most of us may have caught “the great resignation train” for various reasons, but we all headed for the same destination, well-being land.

While most of them claimed to have worked on themselves during the pandemic, working to become more resilient and open to the world, I however couldn’t see anything else other than an egotistical strapline - “me, myself and my mental health”.

I started wondering what on earth they had learned from those wellbeing retreats and personal development books, on their journey to self discovery. Although I appreciate the need to look inward to grow, sometimes it is necessary to pay attention to the outside world too. After all, what is the point of becoming a better version of yourself (I hate this concept) if you are going to be the only one who is going to enjoy it?

I don’t know if it was the music or the fact my social battery was running out, but I started wondering if too much emphasis on wellbeing and mental health at work could have serious detrimental effects?

Okay - being pampered and having reasonable flexible work arrangements sounds like a good plan, but could this also disempower us (employees) and make us exceedingly entitled? I am not an advocate of the JFDI approach, but it does have its merits such as being active and owning one’s own actions, as opposed to being in self contemplation mode.

After listening to a never ending exposé on why companies can do more and should be responsible for their employees mental health, I decided to interrupt my ex-colleague’s monologue by asking two very simple questions:

Why do you rely so much on your company to take care of something so personal and important to you?

If your wellbeing is so important, what are you doing to make your work environment a better place?

Seriously, I’d had enough.

And as if a massive door had been slammed violently, a blatant silence mixed with an excruciating malaise settled over the conversation.

There was nothing to say. Nothing to hear. So I sipped my apple juice and just like that, Nabil left the party.